The length of a single task is notoriously difficult to estimate. But without an insertion ritual estimates don’t even matter because no one consults them. It’s a free-for-all.

Over a year ago I was part of a committee trying to improve our “on time performance.” Our conversation took me back to the heady days of my internship at Novell. Funnily enough, my old manager from that job was there. He had once given the same well rehearsed speech that another senior manager was giving:

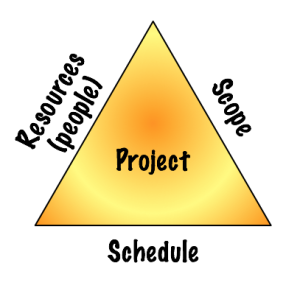

The Golden Project Planning Triangle of Gold

Let’s review the storied planning triangle that every technical person ought to be familiar with. When you plan a project there are three major components: scope, schedule, and resources.

Resources includes people. We know they are people. Please look beyond the fact that they are called resources. We love you all as the individual and wondrous snowflakes you are.

Visual learner? Here’s the picture:

(I made the triangle golden because it’s THAT important.)

That senior manager taught me this:

“On Time” is as basic as following this rule: Always insist that the person requesting to change one aspect of the triangle also tell you how the other aspects of the triangle are to change in order to maintain plan integrity.

… wow, after reading that sentence it doesn’t sound simple. Read it a couple of times if you have to. It really is simple.

For example: You want more feature (more scope): what feature would you like to drop? or What money do I get to hire more people? or What other project is going to slow down as we borrow their developers and testers?

Commitments that have hard deadlines prefer to NOT change the Schedule

The only thing remarkable about a hard deadline commitment is that you can assume the stakeholders are more willing to change scope and resources than they are to change schedule.

For example, when a key feature was to be released it wasn’t translated into all the languages we wanted. It didn’t meet scope. The key stakeholder made a choice: ship it now and we’ll catch up on those languages.

Other than the preference to keep schedule constant, a hard deadline commitment should be no different than any other commitment. And even so, stakeholders may very well choose to sacrifice schedule anyway.

Stakeholders want to choose

Even though it is uncomfortable to confront the fact that you can’t have everything you want, when you want it, without spending any more – even though that’s an obnoxious choice we all hate – there is something we hate even more: when someone else makes the choice for us.

No matter how much you wish you could buy both cars, you would still prefer making the choice than having the dealer say, “No problem, we will deliver them both to your house next week.”

Only to have just one show up.

A month late.

Missed Deadlines? The Issue is Plan Integrity

When I heard the term “hard-deadline” it made me think of padding schedules and cutting out rounds of experimentation. Who knows, it might still involve some of that. But that’s not the real story.

It also made me think that on top of all the other inflexibility in the golden triangle now we can’t change schedule either. Now I see that’s not the case at all.

The real problem is that we don’t consistently maintain plan integrity. Things are added to the plan without forcing a decision about schedule and people. Some teams don’t even have user stories sketched out for work less than a month away. How can you force a discussion about trade-offs when the plan doesn’t exist? Or is so outdated that it can’t make the trade-offs clear.

Everyone needs an insertion ritual

Every person that makes commitments needs an insertion ritual. When someone asks you for another commitment then follow that ritual. It should force the new commitment to be viewed in context of existing commitments and forecasts.

For example, a team mate had a simple board with sticky notes on it that looked liked this:

| Developer | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun |

| Aaron | Proj1 | Proj1 | Proj4 | Proj4 | Proj4 | Proj4 |

| Jack | Proj1 | Proj1 | Proj5 | Proj5 | Proj5 | Proj5 |

| Brad | Proj2 | Proj3 | Proj6 | Proj6 | Proj6 | Proj7 |

(See how all three aspects of the plan are represented and easy to reason about?)

His insertion ritual was simple:

President comes in with Project X and he’s excited. Manager says, “OK, that’s two stickies. Here’s the board. Where do you want them?” The president doesn’t want to give any of them up. Manager asks, “Would you like me to add a couple of months to the board?” No. “Would you like me to add another row for a new developer?” No. Finally the president nixes a project on the board and places his sticky notes. The trade-off is clear.

A prioritized backlog of relatively sized work units facilitates the insertion ritual

Consider having an estimated backlog of work for at least the next 3 months. When someone asks to add something to the backlog make them pick its spot. Appraise them of the estimated completion date. For hard-deadline commitments I would also use a more conservative velocity estimate, perhaps one half normal velocity. … But I’m jumping to solutions. I’m a man AND a developer. Double Jeopardy.

Who knows what other great ideas you will come up with. But I’m pretty sure a backlog, priority, and estimates will be involved.

Stay limber

If people need a hard deadline from you don’t assume you have to ditch agile for something with more prominent planning artifacts. Hard deadlines are still very compatible with Agile development.